The European University Association (EUA) published a report on university autonomy in Europe, including a country profile of Switzerland.

The EUA, who represents more than 850 universities and national rectors’ conferences in 49 European countries, published a report on University Autonomy including several country profiles in October 2023.

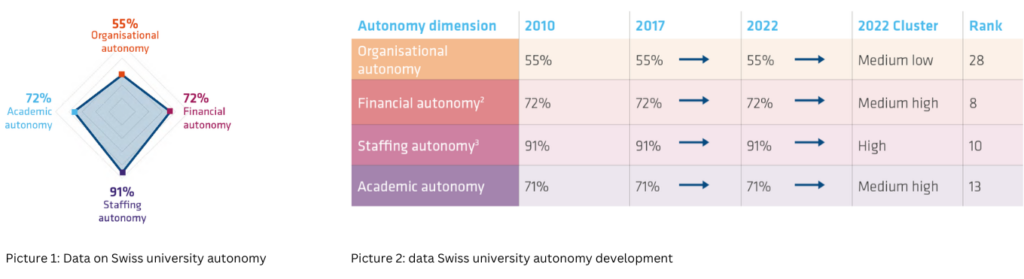

To measure university autonomy, EUA utilises their Autonomy Scorecard, which offers a methodology to collect, compare and weigh data. The Scorecard is based on more than 30 different core indicators in four key dimensions of autonomy, including: (i) Organisational autonomy covering academic and administrative structures, leadership and governance; (ii) Financial autonomy covering the ability to raise funds, own buildings, borrow money and set tuition fees; (iii) Staffing autonomy including the ability to recruit independently, promote and develop academic and non-academic staff; and (iv) Academic autonomy including study fields, student numbers, student selection as well as the structure and content of degrees.

In its newest report, the EUA composed different country profiles, concerning the autonomy of their universities. The country profiles contain information that allows both a comparison of the 35 higher education systems and a more detailed understanding of each individual system. While the main emphasis is on providing a comparative view, the profiles also offer some specific insights. The profiles were developed by using data collected from its members, such as national rectors’ conferences and university associations. This data collection process involved a survey, follow-up interviews, and interview reports. Overall, the 2023 Autonomy Scorecard encompasses 35 higher education systems. For Switzerland, country profiles on university autonomy have been composed in 2011, 2017 and 2023.

Regarding a comparative analysis of the relative ranking of Swiss universities in comparison to their European peers, it can be stated that when it comes to Organisational Autonomy, Finland ranks first with 93%, Switzerland comes second last with 55% followed by Iceland with 45%.

Concerning Financial Autonomy, Switzerland ranks first (72%) and second comes Denmark with 69%. As for staffing autonomy, Sweden has the highest score with 95%, second comes Finland with 92% and Switzerland ranks third (91%). Regarding academic autonomy, Finland has the highest score with 90% and Switzerland is in the eighth place (72%).

Taking a closer look at the country report of Switzerland, it is important to highlight that the evaluation focuses only on the cantonal universities, thus excluding universities of applied sciences, teacher education universities and the two federal institutes of technology. In total, Switzerland has 10 cantonal universities, where a total of 168’000 students are enrolled. This makes up 48% of the student population in Switzerland.

Moreover, it can be indicated that the Autonomy Scorecard has not recorded changes in any of the four dimensions of autonomy since 2010, owing to the general stability of the legal frameworks governing the higher education sector in Switzerland. However, given the diverse regulatory landscape, the analysis is based on an average.

Focusing first on organisational autonomy, Cantonal universities can amend their statutes without public permission or confirmation, using various internal procedures. However, each university is governed by an individual regulatory framework, the modification of which requires approval from the cantonal parliament. Regarding executive leadership, Swiss universities elect rectors through the board or senate, with preliminary selection conducted by an internal body. Depending on the canton, the law may include provisions on the selection procedure itself. The ultimate decision must always be approved by an external authority.

The second indicator is financial autonomy. Cantonal administrations often provide universities with grants for four years, with no constraints on internal allocation. Cantonal universities get public financing for teaching, research, infrastructure, and special initiatives, as well as from other cantons that send non-resident students. Financial elements of the Federal Act on Funding and Coordination took effect in 2017. This act notably granted universities of applied sciences and arts slightly more freedom regarding the allocation of funds. Swiss universities may keep a surplus of public financing, however, there are constraints limiting maximum equity capital: excess amounts must be paid back to the canton or used for specific purposes.

Third is the indicator of staffing autonomy. Swiss universities often recruit senior academic and administrative staff, with cantonal variations. Civil servant status has been eliminated in universities nationwide. Wages vary per canton, often fixed for one or two years but subject to inflation adjustments. Universities can set salaries within cantonal and federal salary categories, as well as promotion rules.

Fourth is the indicator of academic autonomy. While admission to Swiss universities is based on free admission, a numerus clausus applies to certain programmes, most notably those in medicine, health, and the arts. Cantonal authorities decide on restrictions on specific study programmes. Public authorities establish admission standards for both bachelor’s and master’s degree programmes. Universities have complete freedom to terminate and create the content of their degree programmes. In 2015, the Federal Act of 2011 on the Funding and Coordination of the Higher Education Sector went into effect. This piece of law established a system of mandated institutional accreditation for all higher education institutions. It is valid for seven years. Universities can select their own accreditation agency as long as they are recognised by the Accreditation Council.

At the moment, a specific point of attention for the sector continues to be the need for clarity regarding Swiss universities’ participation in the EU’s research and innovation framework programme. In Horizon Europe, Switzerland is currently classified as a non-associated third country. The Federal Council’s goal remains full accession to Horizon Europe. While Swiss universities perceive the general position in terms of autonomy to be satisfactory, they are apprehensive of the unpredictable political context (Covid-19, war in Ukraine, demography) and the pressure it places on institutions, particularly in terms of funding. Despite these disruptions, the sector is confident that protecting autonomy is seen as a key objective for all stakeholders.