The ERC-funded project Locus Ludi explores the role of games in ancient societies and what they could teach us nowadays – a short retrospect reveals the impressive results.

Games are an integral part of human behaviour, a way social bonds are formed and social rules learnt. Even if Christianism established the idea that games are just a waste of time, games are a great way to connect to our past, as Veronique Dasen, Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Fribourg does in the context of the European Research Council (ERC) project Locus Ludi. For her, ancient games reflect the gendered, religious, economic and political fabric of societies which shaped players’ lives by transmitting cultural identity and intangible heritage.

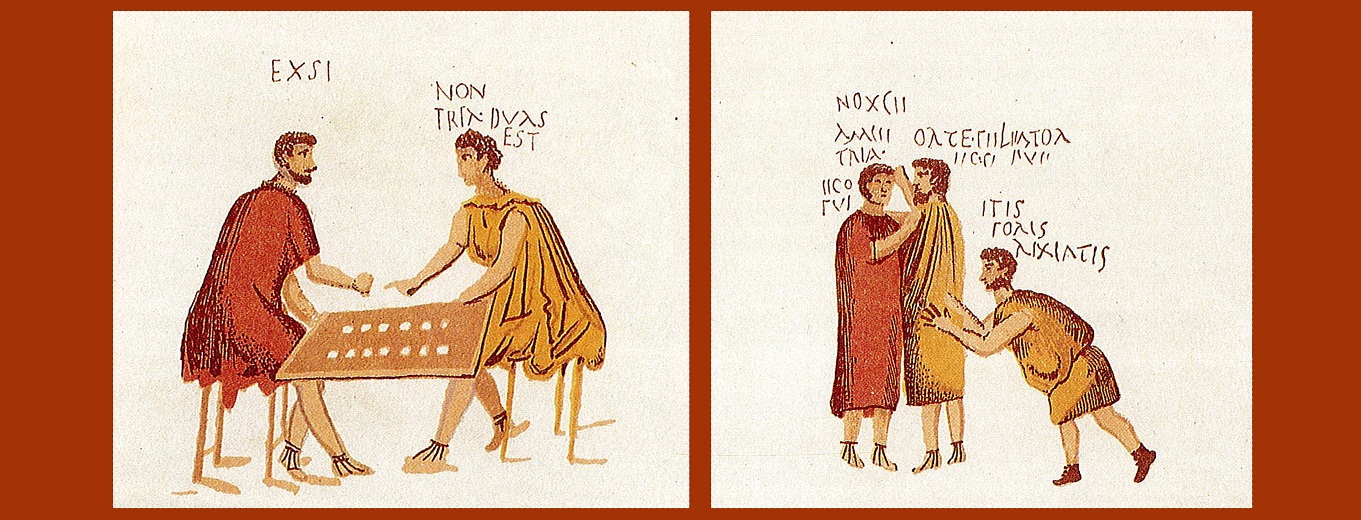

But the question is what can an urn of a woman who died nearby Rome in the first century, depicting a couple playing a board game, tell us about the players, their relationship and the time they lived in? Actually, a lot: taking into account the inscription of the urn, you get to know that the two players are Margaris, a slave and her owner, Marcus Allius Herma. Both are playing the strategy game called “Little Soldiers”, which is well known from descriptions in Roman literature. However, the picture tells much more than that, as Dasen phrases it: “The image of the board game shows intimacy, it is a very beautiful thing because she is a slave, but she is also the beloved one and the leader. The game is also a message to say they wish to be together forever”.

It is one of many possible ways how pictures and literary descriptions of games or playthings can be used to understand the past better. Nevertheless, this rich source of knowledge was ignored for a long time. The only major work in the field is a book from 1869, which also inspired Dasen to develop her ERC project Locus Ludi which started in 2017 and will finish in September 2023. “Except for this book, we knew nothing and were just repeating over and over what was already written.” The ERC grant was especially rewarding for her because “it was a high risk, high gain” idea. Either the project succeeds and fills this long-existing gap by providing the first comprehensive study of written archaeological and iconographic records of games or finds almost no new information. “In the end, the project was a full success.”

With her ERC funding, Prof. Dasen set up an international and pluridisciplinary team with researchers from all over Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, and Italy). “We also had many collaborations with European and extra-European scholars (Great Britain, Poland, Israel, USA, Spain, Marocco, Finland, Hungary, Ukraine) and all brought different trainings, experiences and expertise with them. This created an environment where we all were able to learn from each other”. By bringing researchers from different disciplines like archaeology, philology, history or anthropology together, Dasen was able to develop new methodological and theoretical models anchoring games as valuable and enlighting research objects in academia.

This is also resembled by the impressive scientific output generated during the project. Locus Ludi produced knowledge published in presently about 17 monographic books and many more papers in journals and diverse chapters in collaborative book projects. This included, for example, the first-ever book on games in Pompeii by Alessandro Pace. Another six monographs are currently in preparation or press, like the soon-to-be-published book by Prof Dasen herself ‘Play as Metaphore. Ludic Images from ancient Greece’. “For me, it was important to diversify the publishing scheme and increase our outreach, so we also prepared special issues in reputed journals, exhibitions, open webinars and were present at conferences.”

The project opened doors to many new projects, research questions, and funding streams. “Many of the interesting and telling objects and texts on games are often forgotten in the storerooms of museums, and nobody really knows how precious they are”. One project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation which started in 2020 is exploring the role and use of Greek and Roman articulated dolls which were singled out by Locus Ludi as they seem to be no toys, but objects with specific ritual functions in nuptial rites. Nevertheless, also other internationally funded projects were established in the context of Locus Ludi, like the MSCA project TEXDANCE from Audrey Gouy from the University Lille, who is studying the role of textiles in Etruscan art.

Like many others, also Locus Ludi suffered from the Covid-19 pandemic, as no in-person exchanges or travels to excavation sites were possible anymore. The one-year extension the project got was extremely important for Locus Ludi, but even besides, the project team made the best out of it by introducing weekly remote meetings with invited guests from different fields, which quickly grew in size, geographical coverage and expertise into a real webinar series. “The people joined and joined until we were about 50-60 people.” And even if this posed a certain risk as often very new ideas were discussed, a solid community was created. Even if these webinars are not taking place regularly anymore, as too many things are happening in the real world, a vibrant community now exists, which makes international cooperation much easier. “When we meet for good at last, it is as if we were indeed old friends.”

One of the key takeaways of the project, which focuses on the Greek world from 800 BCE to 146 BCE and the Roman world from 500 BCE to 500 CE, was that these two cultural episodes are not as similar as often thought of. This already starts with terminology. “We started to deconstruct the vocabulary used in Greek and Latin for play and games and found that the terminology differs tremendously”. Greek has two words for play, separating “paidia”, which means games played by children and adults for free enjoyment, and “agôn” or “athla”, competitive activities, organised by the cities for the best ones, involving prices and high social status as for the winners of the Olympic games. In comparison, Latin knows only one word, Ludus, which includes these two kinds of activities as well as the ideas of leisure time and education. But also the games played and the objects used for them differ a lot. While in Greece, thousands of knucklebones were found in tombs and the streets and did have an additional symbolic and religious value, they were rather rare in Roman culture. Meanwhile, dices, even rigged ones, were extremely common in Roman contexts, but rare in Greece.

The project also reevaluated established opinions. A relief carved on the altar of a man called Phanaios which was long thought to show a game scene between a man and a boy, got a new twist during the project. Veronique Dasen commented “It never made any sense that it is a game scene because in ancient Greece, adults did not play with children”, so the relief must have shown something different. In collaboration with Jerome Gavin a mathematician, it got clear that the game board was actually a monumental abacus like it is found in temples or shrines and which was used to perform calculations and not a game board for the Five lines game (Pente grammai), an ancient game as it was thought before. Together both researchers could identify the scenery as one of the earliest depictions of a math lesson, provide a better understanding of how these abacuses were used, and assess that math and play could be culturally associated. “One could enjoy playing on the five lines board after having the lesson.”

In the frame of Locus Ludi, texts and depictions were also used to reconstruct five ancient games. In collaboration with the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and professional programmers in Germany, these were translated into online games accessible to everyone. “It was one of the aims of the project to provide scientifically correct material for a wide audience”. This was not only for fun reasons but to allow using the new knowledge in educational settings, like in schools, libraries or universities. “My dream would be to have a proper video game based on these where you can navigate in ancient cities, play these games at the places where they were played, a palace, a tavern, the forum or a sanctuary, with a story board allowing to understand the ancient cultures better. Unfortunately, our project time runs out” so this plan has to wait until another funding source is available.

The idea of using the findings in the educational context is not restricted to the online games but goes even further. “Games like Pente grammai were used in antiquity to teach children and help them to understand the abstraction needed for mathematics, so we want to try them in schools as well.” The first tests in schools, before a larger study is started, were successful. Beyond that, also other platforms are used to bring the findings to the educational context. For example, with an exhibition on maths and games which is currently being prepared for the Musée Suisse du Jeu in La Tour-de-Peilz. Overall, Locus Ludi is an impressive example of using a mono-beneficiary research grant, like the ERC, of fostering international collaboration and cooperation, bring forward new ideas and theories and connect this with the educational landscape while being engaged in games.

Picture source: Alessandro Pace, Ludite Pompeiani